A day course exploring the impact of the Munich Agreement on German speakers in Czechoslovakia, examining the work of those assisting them to seek refuge in Britain and outlining their experiences and cultural activities once arrived.

Slide 1

The English version of Revolt of the Saints has an unusual history as it was written in German in 1943, translated into English in Mexico and published in England in 1946 with an altered ending to appeal to a Russian audience. So although there are some mistakes in the text, both of translation and typographical, it still makes for a fascinating and absorbing read. It did make the proof reading quite difficult and some errors have got through, but thankfully they do not detract very much except in one instance of a mistranslation where the sentence did not make sense.

Jennifer Taylor kindly translated the original version of the book’s ending, which makes the total result even more historically interesting.

My mother, Claudia, never spoke German to us at home, despite it being her first language, because, as she told me, she was afraid of speaking German so close to the end of the war. I am very bad at languages and have always regretted that, because it means that I cannot read Ernst Sommer’s books in their original German. In fact, in order to do them justice, I would need to have a very good mastery of German, covering religious, historical, psychological and ethical terminology. My discovery of the mistranslation was simply, as said, that the English, though sounding grand, made no sense!

Slide 2

The paragraph that jumped out at me and that I re-translated using Google translate was “Selig sind die Unbefangen, sagte er feierlich und trat in die Endlosigkeit des Korridors hinaus. Sie allein werden den Mut zur Unbarmherzigkeit haben.” is translated as “Blessed are the unprejudiced,” he said solemnly as he went out into the endless passage, “for they alone will have the courage to be merciless.” As I read the paragraph again and again I realised that the faulty word was probably “unprejudiced” and I was right. The paragraph should read “Blessed are the uninhibited, he said solemnly and stepped out into the endlessness of the corridor. You will have the courage to ruthlessness alone”, though I prefer the words, “the courage to be merciless” with the end result as “Blessed are the uninhibited, he said solemnly and stepped out into the endlessness of the corridor. You will have the courage to be merciless.”

I will go into the context of this particular passage in more detail later on as Wolf, the man who thinks those words and who is one of the Book’s heroes is actually a Christian with Jewish heritage and his thoughts are based on the New Testament Beatitudes spoken by Jesus.

Slide 3

I know I am meant to be explaining a bit about the process I went through to republish Revolt of the Saints in the English edition in the UK and rather than leave that at the end, I will give you a very quick synopsis now. I must admit I rather liked the idea of becoming a publisher, but after numerous proof readings and form filling I gave up on that idea very fast! All I had was a rather expensive copy of the book and did not want to risk harming it in order to get reproduced and available for sale. I also, wanted to achieve publication as cheaply as possible. That was why I opted to publish it in electronic form, I Googled companies who could help me and felt attracted to a particular company in Brighton. No idea why. They just felt right and, in fact they were very helpful, so I have no regrets. https://ebookpartnership.com/ It was called ‘ebookPartnership’.I simply took my precious manuscript down to Brighton in person, where they had the equipment to copy the text without damaging the book. I was then able to leave the start of the process to them. They turned the copy into editable text and so my laborious work began. I had to pay for this work to be done and for the final document to be converted into an e-document necessary for the various e-book outlets as well as apply for an ISBN number so that the book would go into the National Archive. Jennifer Taylor kindly produced an introduction and biography for me and so it went onto Amazon and other outlets. I think my publishing career is at an end. You are welcome to ask more questions about this at the end if you want to.

But to begin at the beginning:

My only memory of Ernst was that of a small child – a fleeting memory of an old man in a wheelchair. Nothing more.

Slide 4

Around the same time I have a much more tangible memory of being taken on the Aldermaston Marches (2) against the Atomic bomb. Those were good memories – a huge threat to us all, yet a rare feeling of safety, happiness and belonging as we marched side by side in rows of 4, often silently.

Slide 5

I remember the terror of seeing the film The War Game (3), in which we were told what to do if an atomic bomb dropped on us – laughable now – and I remember being haunted by it and, as I got older, the fear of being separated from my loved ones in such a scenario. I also had other fears that were more difficult to place. Other fears or half memories about what it must be like crammed with others in a cattle truck unable to protect my children or the separation involved in a concentration camp. And yet my mother, rarely spoke of her past or her forced separation from her homeland, friends and comfortable life-style.

Slide 6

I was not brought up as a Jew. My mother, Claudia, was a secular agnostic and she married a man who had been a Christian, but could not cope with the guilt he felt imposed on him by that religion, so he became an atheist. We moved from West Hampstead to Golders Green when I was just 7 years old. It felt like the most miserable day of my life and the end of my world and, looking back, I was right, but that is another story. The important point is that Golders Green was and is very Jewish and that at the end of our road there was a very orthodox synagogue with a large congregation of bearded and large-hatted men who walked past our home every Friday and Saturday and who were held in utter contempt by my father. Our neighbours were Jews, yet my mother never identified with them. Later I understood that she was both afraid and ashamed to admit to it. Afraid, because of the Nazis and all that she had suffered, and ashamed, because of how the Palestinians were being treated by other Jews and also, perhaps she too felt alienated by such outward manifestations of their piety.

I think you can begin to see some threads forming here. My father had been a pacifist in the war, both parents were members of the Liberal Party and, for all my bad memories, I applaud their commitment to anti-war, unilateral disarmament and social justice.

But it was a very long time before I was even aware of Ernst or his books and longer before I understood anything of his politics or theology. Later still before I started to untangle my confusion about my identity – who or what I was and where I belonged. In fact it was not until I was married, living in Hampshire with two adult children, a member of a Christian congregation and a Social Worker, that I began to make sense of anything at all.

All through my adult life I suffered from dreadful bouts of depression and also some painful experiences that mirrored the rejection and heartache I suffered as a child. There is a saying that whatever does not kill you makes you stronger and in my case suicidal thoughts also became inner strength. I have always had a deep feeling of being called in some way (common enough I know), but I felt deeply that I needed to heal my family history somehow and much more than that. I also had a deep-seated idea that I should spend 3 months in Palestine. Yes, exactly 3 months!

Slide 7

One day in 2008, when life felt very tough indeed, I received an email notification of a voluntary job that I could apply for, serving in Palestine for 3 months as part of an international team under the auspices of the World Council of Churches. My life changed dramatically again at that point.

So, after superb training by the Quakers here in the UK, I joined a team of 4; a German, a Canadian and a Swede, for three months living and working in Hebron alongside Palestinians as an Ecumenical Accompanier. You can look EAPPI up on Google to find out what we did as that is another story! (My handout gives various web-sites). (4 & 5)

Not only did I experience at first hand the huge injustices of the occupation, but I learnt a great deal more about my Jewish roots and even experimented by going round Jewish archaeological sites (6) (many uncovered after the forced demolition of Palestinian villages) while putting myself firmly in my Jewish shoes and trying to imagine it all from a Jewish perspective. I also started to read more widely and to find out much more about Ernst. I even found myself working alongside Israeli Jewish human rights activists and came to realise that they were among the bravest of all activists, working against the tide of Israeli policies and opinion.

The theological and philosophical questions raised by Ernst in Revolt of the Saints, have not changed. They are as pertinent for the Palestinians, and so many others around the world, as they were for the Jews, at least those who have any opportunity for revolt and action against their oppressors. They are also pertinent for each of us in our everyday lives and the choices we make.

Slide 8

Revolt of the Saints hinges on a passage in the Old Testament Book of Job. One of the Jewish workers is told that he must leave the camp and be replaced by another. All knew what that meant. It was a death sentence, and not just a quick one, but a particularly cruel end. All living in the camp lived with the utter terror of it, though none knew the details. Knufer, the condemned man, asks the community leader to quote from the Book of Job and there is a brief discussion between those present about God’s response to Job’s complaint. Knupfer’s response is that we must learn to bear our suffering without judgement. “and quietly, as if betraying a secret, he spoke that verse which refutes, renders untenable and deprives of justice all of Job’s accusation and protest: ‘And though he were to strangle me, yet will I surrender myself to him'”

The question Ernst Sommer asks again and again with a variety of answers, is whether direct action against the oppressor is the right thing to do, especially when any action will almost certainly bring about collective punishment on others innocent of such action, who might have been opposed to it.

Slide 9

I know that there are those who have been very critical of Jews who apparently did little or nothing to try to change things; who seemed to just accept their lot, and there are others who condemn Jews such as my grand-parents, who thrived in German society and who, in integrating, lost their Jewishness as a result. If you go round Yad Vashem – The Holocaust Museum, (7) in Jerusalem, then you see some of that derision. The hankering after the traditional Jewish way of life of the Shtetl in Eastern Europe that Jews like these had abandoned only to find themselves condemned along with those who had kept the faith. So for many Jews, the ones that count and are lauded, are those who religiously hung onto their faith and who fought back whatever the consequences, in opposition to the words of Job.

Sommer draws out through the different personalities, beliefs and backgrounds, the different opinions and positions on this subject of resistance or acceptance. In doing so he analyses the practical, the psychological, the moral, the philosophical and the theological considerations necessary for such a decision. On a psychological level, just how bad do things need to become that life, if you can call it that, is so utterly intolerable and the prospects so utterly bleak, that the only two options are to die a slow death or to die fighting. Jan, the son of a Southern Moravian vintner, more attached to his vineyard than faith in the Law of his rabbi ancestors says: “Don’t misunderstand me. Life’s eternal nature is its will to endure. As long as man manages to eke out his life, he uses every chance. But when he realises that he is lost? That nothing more is to be expected but the unbearable? Must not this make him change his resolve? When that which happens to him is nothing but the specific kind of destruction imposed by the enemy—must he not take charge of his own death, and perish the way he chooses?”

So what does it take; how bad do things have to become before that answer is all there is. But even then there remains the moral dilemma, what is going to be the fate of the survivors? Quote “A quick death helps nobody but ourselves. Because of ourselves, others may have to die a much slower and harder death.” So the question is not about life and death, but the manner of the inevitable. But even then, there are those whose faith is so deep and so conditioned in them, such as in Luria, that he cries, “”The Law forbade senseless struggle. Rebellion was alien to the Jewish community. Woe to the Jews who lost patience. To lose patience was to lose faith. God himself withdrew his hand from the impatient. He expelled him and left him to his fate.”

But are such commandments still valid in a situation such as this, Donner asks? “Only the brave are entitled to a decent death”, he says.

For the first half of the story, the manager of the factory employing these Jewish labourers is a man called Schilling who is cold and calculating, but confident enough of his own ability to get the best from his workforce, in the same way that he would with animals or machinery. In fact, when he is told to increase output, he ponders hard on how best to achieve the demanded results and he experiments on his workers to find the best method. He tries very harsh and abusive methods on a man, Jacob, and a woman, Camilla, to see if he can improve their performance by threats, but soon discovers that it has the opposite effect and that their fear and hopelessness actually reduces their productivity rather than increasing it.

So Schilling decides, in a calculating manner, to be ‘kind’ to his workforce. He asks them to improve their output, by making them partners in the endeavour, coaxing and talking to them rather than threatening them. When Jan, his first guinea pig panics as he tries to do as he is bidden, Schilling tells him to pull himself together, rather than threatening him. The appearance of humanity in Schilling gives the Jews hope and makes them want to achieve results for their master. They find hidden strength and almost joy. The result of Schilling’s experiment with his workforce is increased productivity . Quote “And how easy to arouse hope in Jews. The smallest inducement was sufficient. Jews were content if given symbols instead of facts. Schilling freely gave them symbols.” “Here was shown the creative power of faith. Because Schilling had spoken one phrase that could be interpreted as humane, humanity was seen in all his subsequent remarks.”

In fact, what Schilling was showing to his workforce was indifference, rather than the contempt he had shown before, but this did not prevent his workers from interpreting the change in a positive and hopeful manner.

During this time, Jan tries unsuccessfully to get the others to take action against their oppressors. He uses the more favourable atmosphere to bring the Jews closer together. But, despite pressure from Wolf to take action he knows that the time is not yet right. The problem is that the majority cling on to a mixture of religious conviction and hope and are not prepared to rock their more comfortable boat.

Slide 10

Hope is an interesting religious and psychological concept, because it is what can keep the human spirit alive in a very positive way, but it can also be utterly self-destructive. The problem is how to recognise the difference. When is hope false and destructive and when is it life-giving? There is the wonderful prayer of the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) called The Serenity Prayer. The best-known form is: God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can,

and wisdom to know the difference.

Everything changes when Schilling takes compassionate leave and does not return. He is replaced by Brigola who has a giant chip on his shoulder, a sense of injustice to himself combined with indignant self-importance and self-righteousness. Quote “The sensitive shame of one who had often been hurt turned into sickly delight in other people’s torment”. “From the outset he contented himself with the part of silent watcher, utilising his temporary presence in the works in order to make his studies. Brigola’s studies were tiny tortures in themselves. His duties required him to issue certain technical orders. He would intermingle such orders with cold scorn, stinging reprimands, hidden menaces, arousing in his subordinates all kinds of unpleasant sensations. He would interrupt them in their work and at the same time reprimand them for their slowness. He would paralyse them and whip them on; force them to run and trip them up; make them destroy what they had repaired and repair what he had ordered them to destroy. He kept adding to their burden, aroused and rebuked hostility, laid traps for them and then derided the prisoners he had trapped.” “Slowly, a rope got around their necks and was pulled tighter. Everyone, unconsciously, had kept some reserve store of energy. Now overwork caused it to dwindle rapidly. Flesh and blood had to contribute their daily supplement.”

And so, instead of productivity rising it diminishes bit by bit and the punishments and dismissals get harsher. Some begin to consider rebellion again, others envy any who die quickly without additional suffering and some just cling onto life by a thread and refuse any action whatsoever. Jan tries harder than ever to get the Jews to combine as one and to take whatever action they can. Luria however, believes deeply that God forbids such action in His sacred laws. Jan counters this argument with: “Every epoch has its own message. And you are bound, not only to listen but to obey. How dare you claim the newer message is worse than the old! No message is less credible than another. Believing is what counts, not arguing.” He goes on to say that, “The attempt in itself was success. If it miscarried, what could there happen worse than death?”

But Jan is thwarted by a man called Engel who is opposed to violence and tells how the Jews had always paid dearly for it, “We have been made defenceless by nature and our own destiny. Yet we have survived despite our defencelessness, and perhaps even because of it. Shall we hasten our destruction by resistance?”

Then Jacob brings up the fate of any survivors of their possible plan. He says: “Because of ourselves, others may have to die a much slower and harder death.” And so the argument goes back and forth among them until a man called Michael speaks up and says: “he who suffers is alive. And he who has ceased to suffer has nothing left to hope for. He will never see his wife and children, parents and brothers again. He will not live to see the day of judgment. He has renounced everything. He has extinguished himself. He has done our enemies’ work for them.” He goes on to claim that the survival of even one of their number should make such action impossible, “Do you want to deprive him too, of possible salvation? Do you want that one man not to survive? Give him his chance! Leave him his chance of being saved. If that one man were to survive, we others shall willingly accept what is decreed for us.” And with that Jan loses his argument.

As it turns out Michael is not what he seems. His arguments, that convince others to follow him are based on his own selfish desire to live, and over the course of time, that desire is the literal death of others. The survival of the one man he refers to in his argument, is himself.

But there is another man who begins to take centre stage and that is Wolf. He is, in fact, a practicing Christian of Jewish extraction. On a very personal note, I can identify with his situation as I too am a Christian who would, were Hitler to be around now, be equally condemned.

As many must feel in similar circumstances, Wolf’s hatred of his persecutors was fanatical. From the outset, Wolf thought of mutiny and revolt. Quote “But he is not the same as the others in the labour camp, “He was ready to strike, no matter what the end would be. He thought that the best among the Jews must feel as he did. But he forgot that he came from a different world; that he might be a Jew by descent, but ignorant of Jewish tradition.” We learn something of his position prior to his capture and imprisonment. Quote “Christianity, while not uniting him to the persecutors, separated him from the persecuted. ‘Could not a free man chose his faith, nation and country?’ He (had) stuck to his rights and duties and refused to go into exile.”

To cut a long story short for the purposes of this talk, life, if it can be called that, gets worse and the punishments grow harsher. Jan decides to take action himself. He is in charge of the movement of trucks between the Labour Camp and the notorious station, from which groups of Jews are regularly and increasingly being sent to some hellish death that can only be imagined. He decides to fake an accident and takes a lorry full of precision instruments down into a ravine, thereby destroying scarce and expensive enemy resources. In doing so, apart from taking his armed guard to death with him, he believes that no one else will suffer because of his action, as no one else could be blamed for it. He is wrong.

Brigola and his superiors guess that Jan’s action was sabotage, partly because Bigola had already accused his workforce of sabotage, when there had been none. The result was that The District Office decides that the employment of so many Jews to do their war work is dangerous and they decide to considerably reduce the size of the workforce. Brigola calls in Michael and tells him to make a list of those to be dismissed. As, once again, he is employed to decide who should stay and who is disposable, he chooses to send away all those who do or might disagree with him and a few more besides. Quote “Only such people must be left in the works as could completely adapt themselves to Brigola—those who were resolved to accept anything in the hope of living to see the happy ending.” However, he is a weak man and confesses his actions to his young wife, Ruth, who immediately alerts the whole camp to the plan.

The result is that once again they are united. They do not wait to find out who has been chosen to stay and who to go, instead they pick up the plan that Jan had devised earlier. Though this time the uprising is led by Wolf.

It is an interesting contradiction in Christianity that, although many Christians see Jesus as a pacifist accepting his fate as a ‘lamb to the slaughter’, the authorities were so afraid of him, of his influence, of his subversion from their comfortable version of Judaism, that they needed to kill him. I personally do not see Jesus as a pacifist. What I see is non-violent radical resistance to an unjust and oppressive occupation. But, once death was inevitable, Jesus did not set out to take as many of the enemy with him as he could, as Wolf does. So perhaps Jan’s self-sacrificial death is closer to that ideal, though even Jesus’ death heralded a roundup of his supporters and sympathisers and much violence has since been committed in his name. Is it ever possible for one person’s self sacrifice to achieve something tangible without some kind of cost to others? As was said of Jesus, one man’s death was a justifiable sacrifice to save the lives of many by reinstating the status quo. That was from both Jewish hierarchical perspective, and from that of Rome. Or, as his followers believed, one man’s death was a sacrifice to save many. There are always numerous perspectives. I once heard a sermon in an Anglican church about sacrifice and what true sacrifice is. At the time I heard it and for a long time I thought it was right, now I am not so sure.

If I sacrifice for others and in the process do not hurt anyone else, then is that true self-sacrifice? If in sacrificing myself I bring others down with me, then is that just egoism, such as in the case perhaps of suicide bombers who do not care who they kill in promoting their cause? As I have already said, it is, impossible for any real sacrifice not to affect others. At the very least it will affect family, loved ones, disciples and the local community, emotionally. If it affected no one else, then it probably would not be very effective at all. If nothing else self-sacrifice is meant to make others think and question. So maybe it is a matter of degree? If my own sacrifice leads to the imprisonment and death of others, then perhaps that is wrong, but then what about the Second World War and, in fact any war? Huge numbers of innocent people become collateral damage to a greater goal or ‘good’. Can that be right or good? If I am a suicide bomber, what then? Is that any more a selfish act than bombing a hospital full of innocent men, women and children, because weapons may be concealed in or near it or maybe enemy militants are among the patients? Perhaps that depends on who the targets are? After all the suicide bomber may be using the only weapon at his disposal and it may be the desperate act of someone needing to alert the world to their plight. Or he could be a member of a group intent on terrorism and mastery. The well-resourced army may be defending an unjust and illegal occupation. If I don’t fight back and just accept my lot for fear of hurting others by my rebellion, then maybe I am hurting them more by allowing the injustice to continue without protest or without announcing it to the world? There are always multiple perspectives, multiple choices and multiple beliefs. As someone who believes in non-violent resistance myself, I believe all violence to be wrong, but then I am not being hugely oppressed or under direct attack. We are all fallible human beings and can only respond in fallible ways.

There do not seem to be any simple answers. One man’s terrorist, is another’s freedom fighter.

Even the purest of motives and the most altruistic of self-sacrifice can lead to terrible carnage and injustice. In the case of Jesus, there were the Crusades and the many immoral wars fought in his name. In the case of the Tunisian market stall holder who burned himself to death, it has led to revolution, civil war and, in much of the Middle East, growing tyranny. Whether the results of such self-sacrifice are deemed good or bad, depends on perspective and outcomes.

Slide 11

I remember the second time I visited Yad Vashem. As I walked around I thought to myself that I was not being affected enough, and then I was, and I grew increasingly bitter about what had been done to us and then about half an hour after leaving, I felt utterly ashamed of myself, especially as the main building opens onto beautiful parkland built on the ruins of a Palestinian village. When you have been abused and abandoned, vilified and rejected and so much worse, then there are two possible responses. The first is to say never again. Not for anyone anywhere, ever. Or you say never again, not for us. Never again will we allow such things against us, and the latter seems to be the message from Yad Vashem.

Is that not the exact opposite of what so many demand of the Palestinians!! How dare you, I hear many say, how dare you, equate the two. How dare you suggest in any way that what WE suffered at the hands of the Nazis can in any way be equated with the suffering of any others? – I am very careful to say Nazis here and not Germans, because not all Germans were complicit and it would be wrong to tarnish all Germans with the same brush as it is to tarnish all Israelis or all Palestinians. Language is such a powerful weapon and words powerful tools for both education and abuse.

Another of Ernst’s books, translated into English in 1943 was ‘Into Exile’. As Jennifer has already said, it is called ‘Into Exile’ because it is the history of the Counter-reformation in Bohemia. What is particularly interesting to me is that the forward to the book is by the then Dean of Chichester. A.S. Duncan-Jones ends by saying:

‘The story has a significance for any reader, of whatever race or land, who reflects on the course of history. First of all, because of this deep religious note, that sounds like a burden through the long drawn drama. Secondly, as a warning. The average man has always been on the side of the big battalions more than he is willing to admit. But the Czech history shows how illusory is the hope of a peace that floats natural justice. The notion that Big Powers can do what they like with Small Powers lies at the root of the troubles of Central and Eastern Europe. It is from that part of the world – and from this illusion – that world-wars have come. Any attempts to deny the peoples of Eastern Europe the right of self-determination, which includes the right of combination, will come up against the Rock which is Righteousness, the justice that demands that nations great and small should alike be free. The sanctity of the individual and the sanctity of nations spring from the same root.’

Sommer ends that book with the words ‘it is the indestructible belief in freedom which is the most precious fruit of exile’.

The Old Testament makes clear in a number of passages that Jews should preserve the freedoms of others as they knew what it felt like to be oppressed themselves. Leviticus 19:34 says: ‘The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt; I am the LORD your God.

From Wikipedia. ‘The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was a disaster for the ghetto residents. The Nazis estimated that 7,000 Jews were killed during the uprising, and another 56,065 captured for deportation to camps. Of these, all but a few thousand were murdered during Operation Harvest Festival in 1943. An additional 7,000 Jews were also captured and sent to the Treblinka Killing Centre, where most of them were murdered on arrival. The remaining 20,000 Jews in Warsaw lived in the rubble and ruins of the ghetto, which was then completely destroyed along with the rest of the city by the Nazis in retaliation for the uprising. Though another formal resistance did not occur, many Jews would occasionally ambush German patrols in the area until the liberation of Warsaw by the Soviets. “When Soviet troops resumed their offensive on January 17, 1945, they liberated a devastated Warsaw. According to Polish data, only about 174,000 people were left in the city, less than six percent of the pre-war population. Approximately 11,500 of the survivors were Jews”

The original ghetto uprising had a large impact on the Jews as a people. It became a symbol of hope, spread across the continent through secret networks of correspondence. The Germans had thought they could liquidate a ghetto of 60,000 people in three days with little to no resistance. Instead, they had found themselves facing an armed force that was able to hold out against the Nazis, not just for three days, but for an entire month. Within a year, rebellions had occurred in several other ghettos, including Vilna and Bialystok. Though these rebellions would often be unsuccessful, thousands of Jews did manage to escape, many of them forming partisan units to wreak further havoc on the Germans. Other rebellions began to break out in concentration camps around the area. At Treblinka, where many of the Warsaw Jews were sent, several prisoners managed to steal weapons and attack their German oppressors. Even Auschwitz itself soon experienced rebellion when members of the Sonderkommando mutinied against the Nazis and blew up a crematorium. These rebels all knew they would be killed, and the rebellions supressed, but they too fought with the same ideals and self-sacrifice as the residents of the Warsaw Ghetto.’

Ernst Sommer’s book is viewed as prophetic as it was written just 18 days before the 1943 Warsaw uprising. The end for the Polish labour camp described by Sommer is all too similar to that of the ghetto. A huge loss of life, yet a dawning hope. Ultimately history may record that uprising as pivotal and maybe essential to the liberation of many.

The story that Sommer tells is as relevant today as it was when he wrote it. If we stand up for justice in areas of great contention, the organisations we work for and the people we work with can be under threat and there is always the question of balance between speaking truth to power and the consequences of doing so. When powerful ‘men’ do nothing then evil prevails. Sometimes it takes the meek and the powerless to inherit the land through armed revolt.

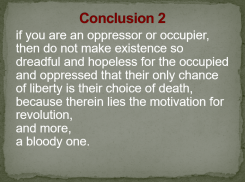

But, of course there is another message that comes from Sommer’s Revolt of the Saints, and that is that if you are an oppressor or occupier, then do not make existence so dreadful and hopeless for the occupied and oppressed that their only chance of liberty is their choice of death, because therein lies the motivation for revolution, and more, a bloody one.

References:

- https://www.amazon.co.uk/Revolt-Saints-Tribute-Heroes-Warsaw-ebook/dp/B00KSDB3PK

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aldermaston_Marches

- http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0059894/plotsummary?ref_=tt_ov_pl

- http://www.quaker.org.uk/our-work/international-work/eappi

- https://www.eappi.org/en

- http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/06/israel-archaeology-findings-ideology-politics-moshe-dayan.html

- http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/museum/overview.asp

8.https://introtogenres.wikispaces.com/What+was+the+result+and+impact+of+the+Warsaw+Ghetto+Uprising.

- ‘Into Exile’ published in London by The New Europe Publishing Co, Ltd. Not in print.